“You can get along very well in this world by coming up with a quantity of reasonably valid statements.”

— B. F. Skinner

Physics and Chemistry

Grinding beans creates two sizes of coffee grinds:

- Fines

- Boulders (or intruders if you’re Christopher Hendon)

For a long time I’ve seen boulders as structural, creating “percolation pathways” through physics and chemistry:

- Fines provide the chemistry. This is where flavour comes from.

- Boulders provide the physics. While the outside of the boulders provide some flavour, the bulk of the boulders provide a physical pathway for espresso to pass through the puck into the cup.

This leads to two generalisations:

- The more fines you have, the more flavour you’ll have in the cup.

- The more uniform the size of those fines, the better the flavour will be.

(Boundary qualifier: while uniformity of size is good, there’s also a certain point fines are so small particle size becomes irrelevant as extraction is 100%)

Which leads to two more generalisations:

- Anything that can create more fines is good.

- Anything that can create more fines and make less boulders is better.

Which leads to a final third rule of sorts:

3) Anything that can do this practically (and preferably easily) is best.

Flat vs Conical

So I always rule out conical burrs for reasons of practicality and ease:

- Some designs retain too much coffee (*cough* Robur *cough*).

- Some designs are pretty damn hard to align (*ditto coughs*)

- Some designs create dust and a lot of boulders ( … *)

So I stick with grinders that use flat burrs.

Chasing Whales

You should really try and align your burrs. Seriously, take the time, don’t stress about it — but align your burrs. It does make a difference, and directly leads to:

- More fines.

- Less boulders.

So align your burrs.

The Resistance of Heat — Much Simplified tl:dr

Grinding creates friction which creates heat. This heat affects your beans. So as the temperature of your grinds increase your fines:

- Decrease in number, and

- Increase in size, with

- Unpredictable uniformity.

No grinder besides industrial roller mills has managed to eliminate this. Some (like the Mythos) aim to constrain heat within a range. Others (like an EK) mitigate this by speed; a typical 20g dose grinding in seconds.

In a high volume environment I’d always choose a Mythos for two reasons:

- The design of the Mythos ensures the grinder itself acts like a chimney, channelling heat out of the grinder, aided by fans.

- This design also enables easy access to the burrs to be cleaned and aligned without much hassle.

Heat still permanently reduces fines, seemingly at odds with “anything that can create more fines is good” generalisation above. But high volume environments will always create heat in your grinder, so at least you have a known temperature range to work within, leading to a higher average of predictable results.

For single origins, decaf, filter coffees, and low volumes I’d go for an EK. It just doesn’t work practically in a high volume environment. For the professionals out there who can do it financially — I’d get both.

I’d use an EK as often as possible for two reasons:

- The design of the EK burrs produces a larger amount of fines, of a more uniform size, than most other burrs — you get incredibly clean and tasty coffee from this grinder.

- While cleanliness and ease of alignment are not nearly as easy as a Mythos, it can still be done in a relatively practical manner.

So if grinding creates friction which creates heat, you can either:

- Work with it. Use a Mythos, and understand what the heat is doing regarding your beans, shot times, and yields — and adapt along the way, or

- Use an EK, and get around issues of heat, while sacrificing speed.

You’ll still have issues with temperature fluctuations of the beans themselves before grinding, along with issues related to freshness, storage problems and the like. So, you could bypass all those issues and embrace temperature control at the expense of speed. Oh, and freeze your beans.

#freezebeansnotpeas — It Really Works.

I look at freezing beans in relatively simple terms:

- Freezing your beans in a standard valve bag is better than not freezing your beans.

- Freezing and squeezing out the air in the bag is better than just freezing.

- Vacuum sealing and freezing is better than freezing and squeezing.

I always vote for ‘3’.

Vacuum sealers are relatively cheap on Amazon or eBay, and you gain some massive benefits from following through with ‘3’:

- Freezing and vacuum sealing stops oxygen degradation dead which

- Allows you to store beans for a longer time.

Additionally, freezing beans and grinding cold gives the added benefit of:

- Narrowing your fines spread — more fines, of an even size — which leads to

- Giving you a known and consistent grind temperature and grind profile so you stay fairly closely dialled in this week, next month, and probably next year, resulting in damn tasty shots of coffee.

I know this works for espresso (I’ve been freezing beans for over a year and a half now) and while I’m no expert on filter brews, ‘a’ and ‘b’ above still apply, and I’m confident the additional benefits also apply.

I’m hoping soon you’ll all be able to see the work Christopher Hendon, myself, and some pretty kickass mathematicians have put together. It should lay to rest a bunch of assumptions regarding low pressure, and show two simple things:

- Low pressure creates higher extraction yields, along with

- Lower variation between those yields.

Put simply — all other variables controlled for — lowering your pump pressure should lead to larger tolerances for mistakes in technique, along with greater extraction potential, resulting in tasty coffee. Tamp not quite a snug fit to your basket? Small angle as you tamp? Distribution a little off? Low pressure won’t magically fix this, but it’ll be far more forgiving of these small errors than nine bars blasting through your puck, while also extracting more flavour.

Puqtastic and Other Poor Puns

This paper will also show you the value of a controlled tamp force. If you hate automation and turned a blind eye as volumetrics, scales, and temperature tags made our lives easier every day — then you probably also failed to notice the Puqpress making it’s way into most high-end coffee shops. For good reason:

- Waaaaaaaaaay less RSI (repetitive strain injury) and fatigue

- The same tamp force applied to your puck each time, every time.

Out of all the variables you need under your control, a consistent tamp force is relatively easy to achieve via the Puqpress, or other tampers like the Eazytamp. Embrace the machines.

Water for Coffee

Water is complicated. No way around it. It’s certainly not dead easy to make your own water for coffee at home, not unless you’ve got a good guide … like this one. It’s also a strange one, caught in a Catch-22:

- You gotta get past the friction of making the water, to taste the difference dialled in water makes — but!

- You gotta taste the difference dialled in water makes, to get past the friction of making the water.

But you really should get past that hump. And you should really buy the book. Of particular interest is Chapter 12: “Roasting to water”. But to understand what’s going on here we need to back up slightly.

We know two solid pieces of information from Christopher Hendon and Maxwell Colonna-Dashwood’s work:

- Magnesium and calcium help extract acids from coffee.

- Bicarbonates help organise those acids.

From this information, we arrive at the vastly simplified rule of keeping a 2:1 ratio of magnesium and calcium (combined) to bicarbonates, as CaCO3.

Delving a little deeper, we can simplify again by stating:

- Too high a buffer relative to Mg + Ca leads to wiped out and dull flavours

- Too low a buffer relative to Mg + Ca leads to aggressive sour flavours.

You could also swap this around:

- Too high a level of Mg + Ca relative to the buffer leads to aggressive sour flavours.

- Too low a level of Mg + Ca relative to the buffer leads to wiped out and dull flavours.

Pivoting again (stay with me peeps!) start thinking about roast profiles. When cupping samples some generalised trends might present themselves. Perhaps:

- The roast is too acidic.

- The roast is too “roasty”.

- The roast lacks body.

- The roast has too much body.

- The roast is too sweet (jokes! No one ever said that!)

- The roast is not sweet enough.

My sincere apologies to all the roasters out there as this is another gross simplification — but there are two points that need to be made here:

- Flavours present themselves based on the water used to cup.

- The water used to cup can have a direct effect on perceived acidity, sweetness, “roastiness”, and body.

So the roaster, upon decrying the acidity of the roasted sample, could instead try to lengthen the roast a little for the next batch and blunt the acidity slightly. Or upon tasting the roastiness speed up the roast, shortening the total roast time. If they wanted less body they might try to shorten the Maillard reaction, or lengthen it to achieve the opposite.

Again, I’m no roaster, but I do know you can manipulate the roast to present different flavours in the cup. So what’s important here is the roaster is creating a roast profile that’s:

- Based on the cupping samples, where

- Flavour is determined by

- The mineral content of the water used to cup the samples.

This is important, because if the water used to brew the coffee is different from the water used to roast the coffee, then you’ll not taste what the roaster wanted you to taste. Which is why Chapter 12 of Water for Coffee is important, and a vastly overlooked factor in specialty coffee.

If you’re not speaking the same “water language” as the roaster — you won’t be tasting good coffee.

Distribution

While it may seem self-evident, it needs to be remembered all of these variables centre on one important aspect: literally, your puck. While we can do all the right things to ensure everything around the coffee in your puck is optimised, distribution of your coffee is arguably the engine room that defines a good run for that particular shot. Like a perfectly porous sponge, we want the brew water to:

- Evenly travel through the puck, to enable

- An even extraction.

But this relies on:

c) An even distribution of coffee grinds.

You could go the distribution tool route, but I’m a bigger believer in the far cheaper alternative of palm tapping. To my mind, this provides the best form of vertical and horizontal distribution of your coffee grinds, over and above any tool on the market at the moment. And it’s free.

Also — if your puck doesn’t look like a PGA Golf tour green when you’re done, then you’re doing it wrong.

At home, and at work when using frozen beans and the EK, I also use a dosing cup to grind into, then transfer this to the basket via a jam funnel (after weighing the dose and correcting). Before palm tapping, I take the extra precaution of literally whisking the beans around in the basket and funnel. How the coffee falls from the chute into the portafilter is going to have an effect on density, just as how the coffee fell into the grinder is going to have an effect on particle size. A whisk is the great homogeniser of both density and particle size, before palm tapping and tamping.

(And for all those peeps out there fronting with combs before palm tapping — at BH we got your back. Stay patient … )

Stacks upon Stacks

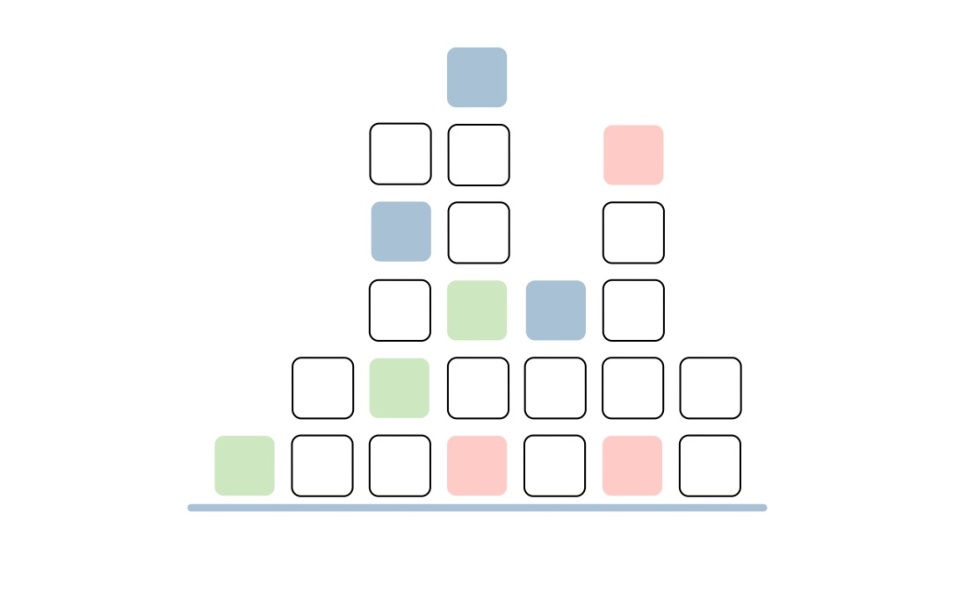

I find a good way to visualise all this so far is to look at these variables as “stacks”. Within each stack is a spectrum, going from good to bad. However, it doesn’t take many of these stacks to veer towards the bad side of the spectrum to spoil every other stack.

Simplifying this, let’s look at the case with roasting and water for coffee. We can generalise this into four stacks:

- Roaster skill: essentially how good is the roaster at turning green to brown, on a spectrum from good to bad.

- Roasting water: what was the mineral content of the water like when cupping, graded on a spectrum from good (a beneficial ratio of 2:1 for Mg + Ca to buffer) to bad.

- Brewing skill: how good is the barista making the brew, on a spectrum from good to bad.

- Brewing water: what was the mineral content of the water used to brew the coffee, again graded on a spectrum from good (a beneficial ratio of 2:1 for Mg + Ca to buffer) to bad.

Four stacks, four spectrums from good to bad. So when you hear so many good things about a roaster, but upon trying their coffee at home it’s just no good, it may be because:

- The roaster kicked ass with this profile, on the good side of the skill spectrum.

- The water used to cup this roast had a beneficial mineral ratio.

- You certainly kicked ass at making the coffee, definitely on the good side of the skill spectrum (right?!?)

- But your water sucks. Maybe too much bicarbonate drowning out what little calcium and magnesium you have in your water, or it’s simply too different from what was used to create the roast profile … So:

e) Your coffee sucks.

You might then apply a rudimentary and flawed scientific process, ignoring your water profile and instead focusing on yields. Or you spend an hour aligning your burrs, or dose weights changed, brew temperatures adjusted. With the same result:

e) Your coffee sucks.

Change the stack out. Now your burrs are out of alignment, on the poor side of the spectrum. But your water, roast profile, pump pressure, tamp force, distribution, bean temperature, etc — they’re all on the good side of the spectrum. But still your problem persists because you haven’t isolated your variables, you haven’t found the problem in the stack where your burrs are out of alignment — so:

e) Your coffee sucks.

These stacks continue all the way down the value chain. How high the beans were grown, their ripeness when picked, the varietal was itself, how it was processed, how it was fermented, how long it was fermented for, how it was transported. All these stacks, each on a spectrum from good to bad.

And imagine if they were all on the good side of the spectrum, every stack, bar one — the beans bought back at origin have sat in the warehouse for too long. So the beans are:

- Stale, yet

- Roasted with skill

- After being cupped to “good” water

- Then brewed by a skilled operator with good skill, yet still

- Your coffee sucks.

Balancing this stack, one above the other, controlling what you can, yet being let down by stacks outside your control, is exhausting — let alone those stacks within your control. Because the key to making great, consistent coffee is built upon:

- Stacks and stacks of variables

- Upon more stacks.

Specialty Coffee and The Next Wave

We’ve done an amazing job of getting our heads around these stacks, of controlling what we can. But I can’t help think we’re entering the final stages of marginal gains for whatever we’re calling this moment in coffee culture. Still third wave? Are we onto the fourth yet? Because to get there I feel there are two fundamental questions we need to answer first, two foundational stacks this is all built upon:

- Preparation of specialty coffee.

- Approachability of specialty coffee.

On a spectrum from good to bad, where do you think both of these sit right now? I really need you to take a step back for a second and think about these questions:

- If preparation of specialty coffee is easy, then who is it easy for?

- And if it’s easy for them, why is that?

- And if specialty coffee is approachable, then who is it approachable for?

- And if it’s approachable for them, why is that?

In the age of social awareness, automation, science, and technology — this is where the next wave is coming from. We’re hitting the edges of the marginal gains offered by the current paradigm of coffee, and to evolve as an industry we really need to be thinking about what this next wave will look like, and the stacks it’ll be built upon.

Because someone will find the right answers to those questions, and if it’s not you then e) it doesn’t matter if your coffee sucks. No one’s gonna be drinking it.

Michael Cameron